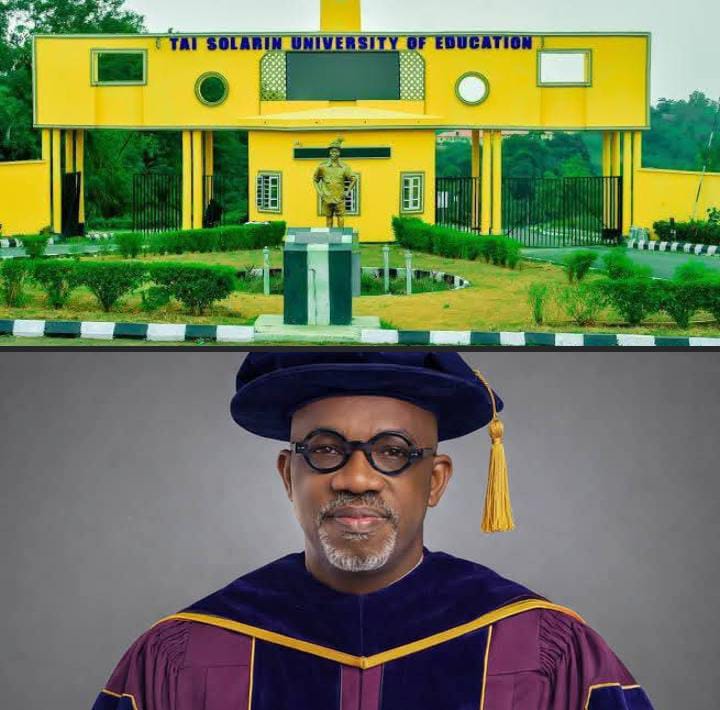

The 17th Convocation ceremony of Tai Solarin Federal University of Education (TASFUED) ought to have been a solemn academic ritual—one governed by merit, memory, and moral clarity. Instead, it has triggered a necessary public conversation about honour, judgment, and institutional responsibility.

Let it be clearly stated: this intervention is not a personal attack on Prince Dapo Abiodun. In African wisdom, “You do not blame the guest for the food served; you question the host who set the table.” The real burden of explanation lies squarely with the TASFUED Governing Council or the Convocation Organising and Planning Committee, whose duty it was to ensure that academic honours rest on deserved heads and historic truth.

An African proverb warns: “When the drumbeat changes, the dancer must also change.” Universities are moral drummers of society. When they beat the wrong rhythm—by awarding honours disconnected from substance—the entire society dances into confusion.

TASFUED is not an ordinary institution. Its existence is a fruitful seed planted by Otunba Gbenga Daniel (OGD)—a vision that survived political hostility, underfunding, and eventual transformation into a federal university. That seed continues to bear fruit in graduates, educators, and national relevance. As Chinua Achebe reminded Africa, “A man who does not know where the rain began to beat him cannot say where he dried his body.” Any convocation that forgets the origins of TASFUED forgets itself.

It is within this historical and moral context that the honorary doctorate conferred during the convocation appears misplaced. Not because Prince Dapo Abiodun demanded it, but because the crown was not placed on the head destiny prepared for it. Another African proverb teaches: “The crown does not make the king; the king makes the crown.” Academic honours are meant to recognise enduring contribution, not current power.

The late Ghanaian scholar Kofi Awoonor once observed that institutions lose their souls when ritual replaces responsibility. Similarly, Prof. Claude Ake warned that when public institutions serve power instead of principle, they betray their foundational mandate. A university that allows political convenience to override scholarly judgment risks becoming a ceremonial extension of government rather than a conscience of society.

Supporters of Prince Dapo Abiodun should understand this distinction. Accepting an honour offered by an institution does not automatically validate the process that produced it. In African ethics, “When a child is wrongly crowned king, the elders have failed in their duty.” The failure here is institutional, not individual.

TASFUED’s Governing Council and Convocation Committee owed Ogun people, scholars, and history a higher standard. They were expected to ask hard questions: What measurable educational legacy is being honoured? What enduring contribution to teacher education justifies this robe? What truth will history record?

As the Kenyan scholar Ali Mazrui cautioned, Africa’s crisis is not a lack of titles but a shortage of earned authority. When honours are rushed, politicised, or poorly justified, they lose meaning—and the institution that confers them loses credibility.

OGD planted the seed.

Time has vindicated that vision.

Prince Dapo Abiodun merely accepted what was served.

But TASFUED’s custodians must answer why the crown missed its rightful destiny.

In the end, “truth is like the sun; you can cover it for a while, but it will rise.” Universities must stand where truth stands—above power, above politics, and above convenience.