On a day in May this year, the head offices of Tingo Group in Lagos had none of the markers of a global multimillion-dollar technology company.

Occupying two floors in a high-rise building in the city’s old commercial district, there was broken furniture, fewer than 20 staff and none of the buzz of an operation with millions of customers.

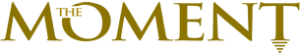

What a months-long investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission found instead was what the US watchdog described as a “massive fraud” involving “billions of dollars of fictitious transactions” — all under the helm of one man: Dozy Mmobuosi.

The 45-year-old London-based Nigerian entrepreneur, who had sought to buy English Premier League club Sheffield United this year, inflated the profits of three companies by forging documents to swindle investors, according to the complaint.

In November, the SEC halted trading in Nasdaq-listed Tingo Group and Agri-Fintech securities after finding inaccuracies in their disclosures. The move followed a report by US-based short seller Hindenburg Research in June that called the company an “exceptionally obvious scam”, and caused Tingo’s share price to nosedive.

“Tingo Mobile is a fiction,” the SEC said this week in a 72-page complaint. “Its purported assets, revenues, expenses, customers and suppliers are virtually entirely fabricated”. The scale of the fraud was “staggering”, it added.

The charges against Tingo are another blow to the reputation of fintech “superapps”, which have emerged in the past decade and sought to disrupt banking by offering payments and other services such as instant messaging and trading. Investors have bet that these new entrants’ most promising growth prospects lie in emerging markets such as Nigeria where the need for banking services is most acute.

“This is the most obvious fraud we’ve ever seen and people just refused to see it for what it was,” said Tunde Leye, partner at Lagos-based risk intelligence company SBM. SBM analysts visited Tingo’s supposed phone factory and food processing plant and found the site empty, Leye said.

On Wednesday, Mmobuosi stepped down as Tingo chief executive and board member as the SEC seeks to permanently bar him from serving as an officer or director of a public company.

In a statement reported in the Nigerian press on Friday, Mmobuosi called the SEC’s allegations “baseless” and said he “will contest them with unwavering resolve”.

“He is committed to co-operating with the legal process to ensure a thorough and fair examination of the facts, which he believes will ultimately lead to his exoneration,” the statement read.

Tingo said in a statement it “intends to vigorously defend itself in relation to the SEC complaint”.

The origins of the alleged scam date to 2019 when Mmobuosi used fake documents to portray Tingo Mobile as a healthy business, according to the complaint. The Nigeria-based entity, which claims it provides farmers with microloans, weather forecasts and an online marketplace, had only about $15 in its account that year, the SEC says.

He then allegedly used these false documents to transfer Tingo Mobile to two public companies at “grossly inflated” valuations.

In 2021, Tingo Mobile was sold through an all-stock reverse merger to OTC-traded Agri-Fintech, which in turn sold it to Nasdaq-listed Tingo Group a year later, also through an all-stock merger. The transactions valued Tingo at more than $1bn and gave it access to US capital markets. Advisers included global law firm Dentons.

Mmobuosi once sent purportedly audited statements of Tingo Mobile to the group’s chair, when in fact no audit had occurred, according to the SEC. The company reported it had a cash and cash equivalent balance of $461.7mn for the 2022 financial year. In reality, it held less than $50 in its accounts.

The entrepreneur had previously sought to list Tingo Mobile via Delaware-registered Tingo International Holdings, which he controlled. But the application was rejected by Nasdaq.

In April this year, Tingo co-chair Christophe Charlier resigned citing his unwillingness to sign off on the group’s financial statements and the “lack of communication and teamwork in the management of the company”.

The SEC alleges that Mmobuosi — who once described himself as a “special kid” while growing up and said he earned the nickname “The General” in secondary school — used the money to lead a lavish lifestyle buying “luxury cars” and travelling on “private jets”.

In Lagos, some say they had expressed doubts about the reality of Mmobuosi’s business. It claimed it had 9mn users, but “almost no one in the industry has ever met someone that uses the product”, said Iyinoluwa Aboyeji, a Nigerian technology entrepreneur.

“Many people called me to ask about investing in Tingo,” Aboyeji said. “And despite expressing my well-established doubts, they still went ahead to invest.”

Asked in May about the company’s customer base, Auwal Maude, head of Tingo Mobile Nigeria, told the Financial Times that the farmers using the app were all based in the north of the country, some 900km from Lagos. The executive could not produce any of the Tingo mobile phones it claimed to distribute to farmers.

Hindenburg started investigating after being alerted by market participants. How a company without a verifiable product was able to attract so much investment in the open market hinged on its Nasdaq listing and the clean audit it received from Deloitte Israel, according to Hindenburg founder Nathan Anderson.

“How many people are going to believe in a Nigerian fintech group that claims to offer mobile services to nine million rural farmers (when) no one can find where any of it was? How do you go from that to Nasdaq and over a billion market valuation? Deloitte and Nasdaq are what lent it credibility,” he told the FT.

The reason why Deloitte Israel audited a Nigeria-based company listed in the US is unclear — the Big Four firm has offices in both countries. Deloitte Israel declined to comment, saying: “Professional standards prohibit our commenting on client matters.”

Tingo also found investors in the UK, pledging to foster “financial inclusion” in Africa and expand in China.

In a private placement presentation that referred to the company’s 2021 financial results, Tingo boasted about a “strategic partnership” with Visa to help with that strategy.

In February, Andrew Uaboi, head of Visa’s West Africa operations, saluted a deal that would “help to digitise the entire value chain for farmers . . . and support the financial inclusion agenda across the continent”.

After the SEC charges, Visa said all its clients and partners are “required to ensure that they comply with applicable legal requirements and regulation” and that it has “a robust process to assess compliance and to work with our clients to address issues that arise”.

In the UK Mmobuosi was helped by Benjamin White, who is registered as the majority shareholder of China Strategic Investments Limited. The adviser, who confirmed he was granted shares in Tingo Group (the first iteration of which was set up as early as 2002) for “consultancy work”, advertised the fundraising before the transactions on the Nasdaq, according to regulatory filings and documents and emails seen by the FT.

White sought to raise more from investors in February 2020 ahead of the US listing, charging a 15 per cent performance fee, telling prospective investors he expected returns of “well over 10x”.

White told the FT that his company had raised more than £20mn in total from investors, who agreed to a performance fee if their returns tripled. He said he was astonished by the SEC complaint. “I have not seen any evidence of a fraud and would be extremely surprised if there was a fraud,” he said, adding he had “not been involved” in any fraud.

Tingo’s founder also enlisted the services of Chris Cleverly, a barrister in the UK with experience working on “white-collar fraud and organised transnational crime cases”, according to his chambers. The cousin of UK Home Secretary James Cleverly became Tingo’s president and board member.

Bilal Brahim, chief executive at Fame, a farmers network in Nigeria, said Chris Cleverly had approached him to buy software, offering to trade about £20mn of Tingo shares. Chris Cleverly declined to comment.

Hindenburg’s Anderson said he had “never seen anything like” Tingo.

“For a decent fraud case, there might be a couple of material misrepresentations where management will try to lie about a big thing or two,” said Anderson. Here what was faked was “an entire conglomerate”.

Source: Financial Times